Return-Free Risk

John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

President, Hussman Investment Trust

January 14, 2022

The main adaptation that deranged Federal Reserve policy required of our own discipline in this cycle was to abandon our pre-emptive bearish response to historically-reliable ‘limits’ to speculation, and to instead prioritize the condition of market internals (which have been part of our discipline since 1988). Essentially, we became content to gauge the presence or absence of speculation or risk-aversion, without assuming that there remains any well-defined limit to either. A more recent adaptation has been to adopt a slightly more ‘permissive’ threshold in our gauge of market internals when interest rates are near zero and certain measures of risk-aversion are well-behaved. The main effect is to promote a more constructive shift following material market losses.

The question isn’t whether one should adapt to unprecedented Fed policies, but instead, the form those adaptations should take. We are fully convinced that these historic valuation extremes have removed decades of investment returns from the future, and strongly suspect that the Fed has amplified future downside risk as well. I believe investors have placed themselves in a position that is likely to be rewarded by a very long, interesting trip to nowhere over the coming 10-20 years. At worst, they may discover the hard way that a retreat merely to historically run-of-the-mill valuations really does imply a two-thirds loss in the S&P 500. Still, our research efforts in recent years have focused on adaptations that can allow us to better tolerate and even thrive in a world where valuations might never again retreat to their historical norms. We don’t actually expect that sort of world, but have allowed for it.

– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., Maladaptive Beliefs, September 2021

In an economy where the Fed has lost every systematic tether to common sense, empirical evidence, and concern for financial stability, it’s worth beginning this first market comment of 2022 by recalling the ways we’ve adapted in order to navigate that environment. In a world where securities are regularly described on CNBC as “plays,” it’s clear is that the financial markets presently have little to do with “investment” – at least not by Benjamin Graham’s definition as “an operation that, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return.”

It may be true that zero interest rates provide investors “no alternative” but to speculate. But as Graham emphasized, there are many ways in which speculation can be unintelligent. The first of these is speculating when you think you are investing.

I cringe when I hear analysts talking as if any dividend yield above zero is “better” than zero interest rates. That argument relies entirely on ruling out even the smallest decline in price, and the smallest retreat from current valuation extremes. The dividend yield of the S&P 500 is just 1.3% here. It was lower only in the quarters surrounding the 2000 bubble peak. The run-of-the-mill historical norm is about 3.7%.

Those of you who are familiar with finance can prove to yourself that the effective “duration” of stocks (the weighted-average number of years needed for present value to be repaid by cash flows, and the sensitivity of the market price to changes in the discount rate) works out mathematically to be approximately the price/dividend multiple. From that perspective, one can think of the S&P 500 as being a 77-year duration investment here, compared with a historical norm closer to 27 years.

Depending on market conditions, stocks can have “investment merit,” “speculative merit,” both, or neither. In our own discipline, we gauge “investment merit” by valuation – the relationship between the price of a security and the long-term stream of expected cash flows that we expect that security to deliver over time. We gauge “speculative merit” based on the uniformity or divergence of market internals. When investors are inclined to speculate, they tend to be indiscriminate about it. Since 1998, our most reliable gauge of speculation versus risk-aversion has been based on the signal we extract from the market action of thousands of individual securities, industries, sectors, and security-types, including debt securities of varying creditworthiness.

The single difference between the most recent market cycle and other cycles across history is that in every other cycle, speculation always had a well-defined limit. We gauged those extremes based on what I describe as “overvalued, overbought, overbullish” syndromes. Unfortunately, zero interest rates have proved to be a kind of acid that burns through every shred of intellect, driving investors to imagine that any asset that varies in price – regardless of how extreme its valuation or how uncertain its underlying cash flows – is better than zero-interest cash. My error in this cycle was to believe that speculation still had well-defined limits. In late-2017, I abandoned that view, and became content to gauge speculation versus risk-aversion based on the condition of market internals. Since then, we’ve refrained from adopting or amplifying a bearish outlook when our measures of internals are constructive, regardless of how extreme valuations might be.

The difference between genius and stupidity is that genius has its limits.

– Albert Einstein

As I observed in September, our more recent adaptations basically amount to criteria for accepting moderate amounts of market exposure – coupled with position limits or safety nets that constrain risk – even in conditions where valuations imply poor long-term returns. These criteria fall into what Ben Graham would describe as “intelligent speculation” – kept within minor limits.

Over four decades of work in the financial markets, I’ve regularly been defensive at bull market peaks, shifting to a constructive, unhedged, or leveraged outlook after valuations plunged toward their historical norms, as they did in the 2000-2002 and 2007-2009 collapses. That flexibility produced beautiful results in previous, complete market cycles. Yet I’ve never seen such conviction among speculators that the good times will never end, or such faith that the Federal Reserve can make it so. I’m quite certain that this is a delusion, but I am less certain about how long that delusion can persist.

John, I don’t think anybody would believe me if I told them that back in the early 1990s I used to refer to you as one of my column’s “resident bulls…”

And then… we started getting charts like this! 😱🤣 https://t.co/sfQmHYkNxb

— Herb Greenberg (@herbgreenberg) December 6, 2021

Until the catastrophic consequences of Fed-induced speculation become unavoidable, the reality is that all we can do is deal with it. For us, our preferred ground is to act on what we view as investment merit, when it is available. When it isn’t, the acceptable ground is to be content – within minor limits, but as often as possible – to accept periods of favorable market internals as opportunities for what Graham described as “intelligent speculation.” The opening quotes details what I view as our best approach to that problem.

We’re certainly not inclined to accept risk regardless of market conditions, but as I noted in September, we’ve also got sufficiently reliable tools, investment criteria, and just as importantly – position limits and safety nets – to accept moderate amounts of market exposure with greater frequency, even in conditions where valuations imply poor long-term returns. The main consideration there is whether our measures of market internals are constructive, suggesting that investors are inclined toward speculation rather than risk-aversion.

Even with the minor adaptations I described in September, our measures of market internals remain unfavorable here. Still, even if valuations remain dramatically above their historical norms, I expect that we’ll see periodic but adequate opportunities to accept market exposure even in the coming quarters, within limits that Graham would endorse.

Return-free risk

By relentlessly depriving investors of risk-free return, the Federal Reserve has spawned an all-asset speculative bubble that we estimate will provide investors little but return-free risk.

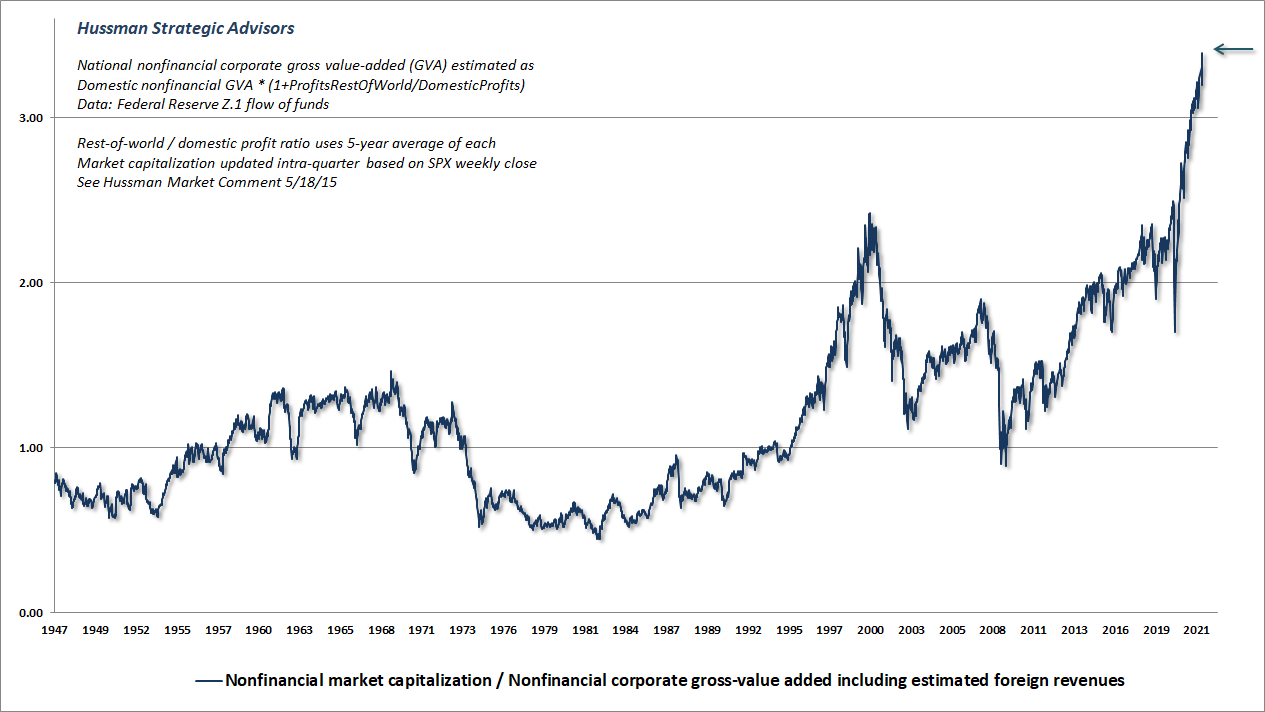

The chart below presents our most reliable valuation measure (based on correlation with actual subsequent market returns), the market capitalization of non-financial U.S. companies as a ratio to their gross-value added, including estimated foreign revenues.

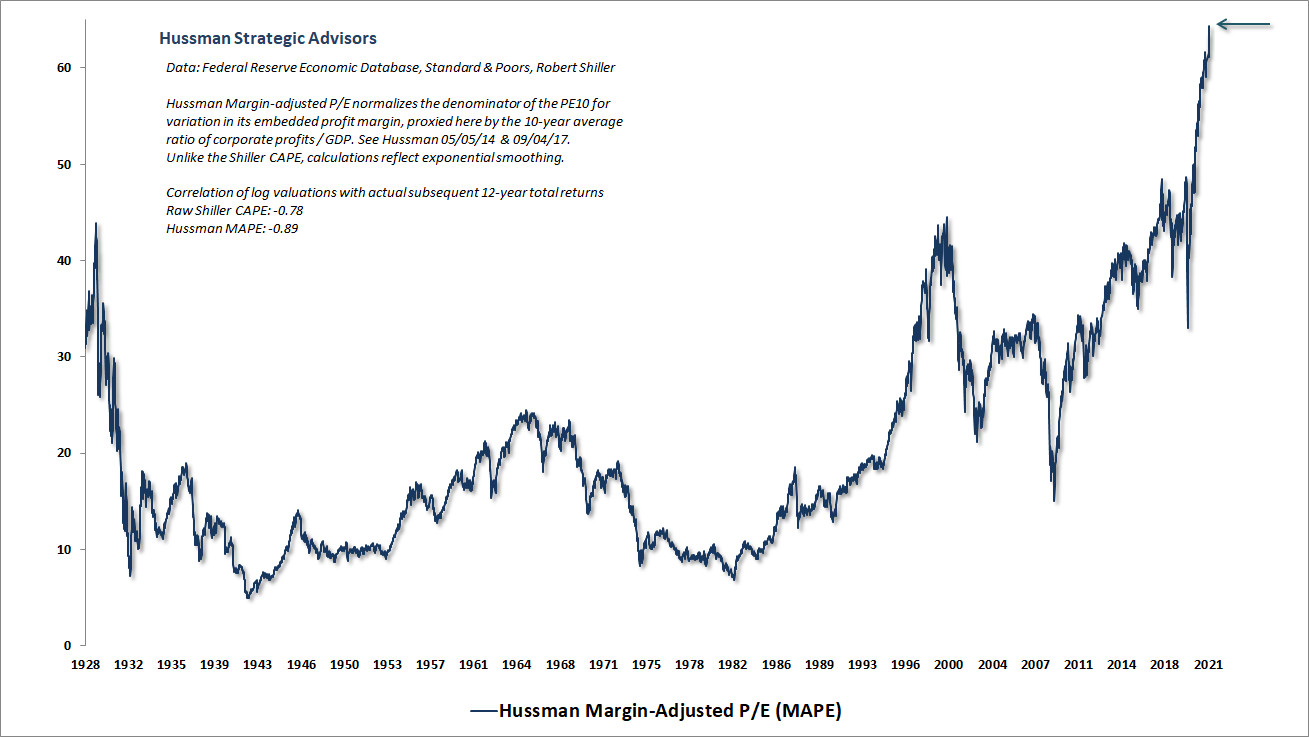

As an alternative measure, the chart below shows our margin-adjusted P/E (MAPE), which has reached extremes easily beyond the 1929 and 2000 bubble peaks. Recall that the S&P 500 lagged Treasury bills from 1929-1947, 1966-1985, and 2000-2013. 50 years out of an 84-year period. When the investment horizon begins at extreme valuations, and doesn’t end at the same extremes, the retreat in valuations acts as a headwind that consumes the return that would otherwise be provided by dividends and growth in fundamentals. Do investors really imagine that the outcome from present extremes will be so different? Worse, do they imagine that loading up on speculative market risk will be rewarded with a “risk premium” regardless of the level of valuation?

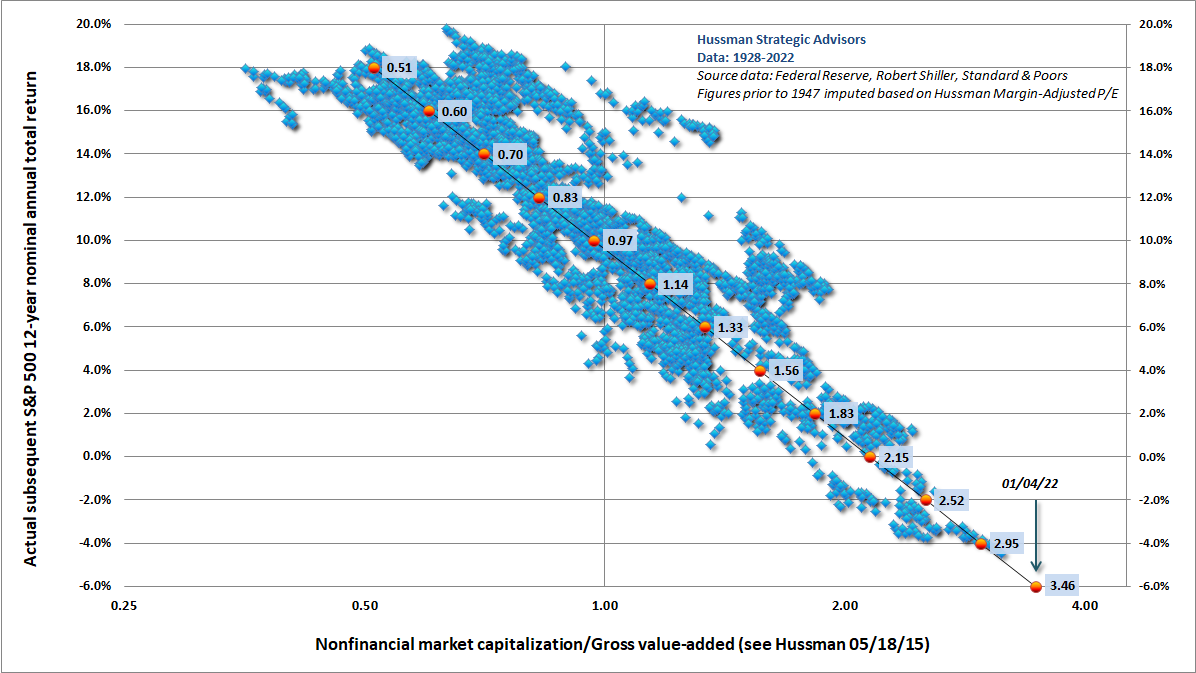

The scatterplot below shows how these valuation measures are related to actual subsequent 12-year S&P 500 nominal total returns, in data since 1928.

Investors are familiar with the idea of a “tradeoff” between return and risk, which is typically stated as a proposition that investors must accept higher risk if they seek higher expected returns. What investors are typically not taught is that this proposition applies only to “efficient” risks. For example, if a portfolio is poorly diversified, one can typically find another portfolio that can target a higher level of expected return for the same amount of risk, or a lower level of risk for the same expected return. Likewise, in a wildly overvalued market, investors should expect not only poor returns but also higher prospective risk. Put simply, investors are not somehow rewarded for accepting higher levels of what Ben Graham described as “unintelligent” risk.

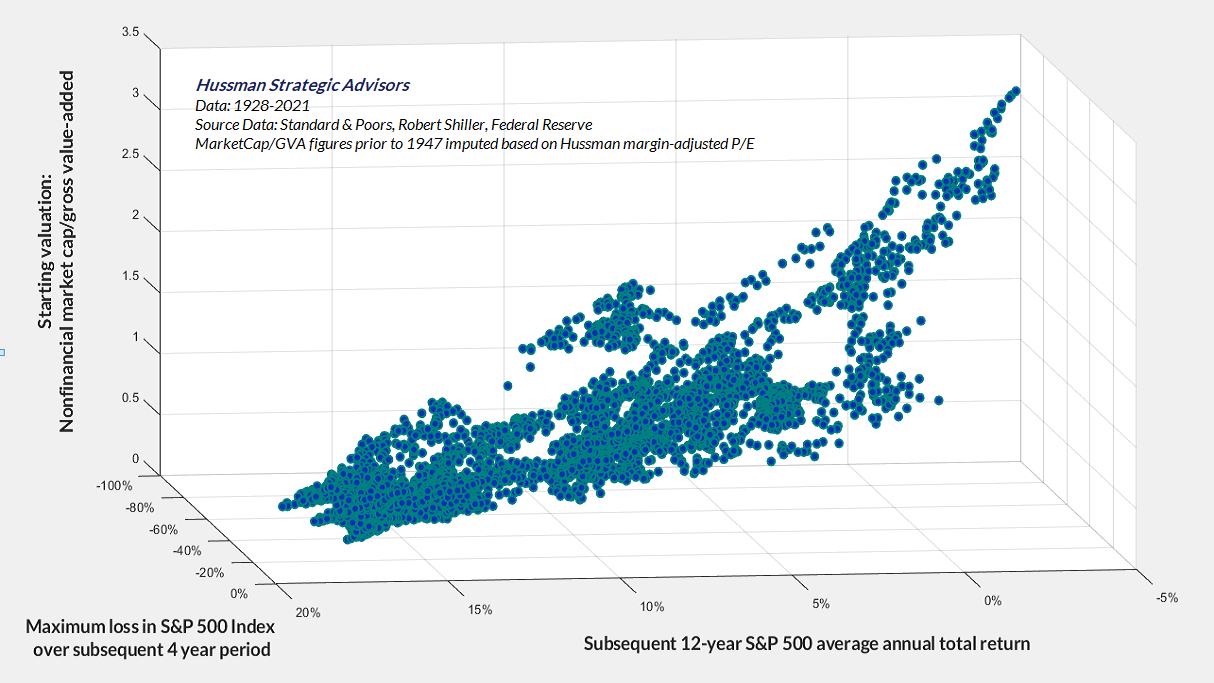

The chart below may be a rather painful illustration of this principle, particularly for investors who have loaded up on equities at record valuations, in the misguided belief that their expected returns will be enhanced by doing so. The chart reflects data from 1928 to the present. The vertical axis shows our measure of MarketCap/GVA – the ratio of nonfinancial market capitalization to gross value-added, including estimated foreign revenues, which currently stands at a level of about 3.4. The axes at the base show subsequent investment outcomes. One axis shows the average annual total return of the S&P 500 over the subsequent 12-year period. The other axis measures the deepest drawdown loss experienced by the S&P 500 over the following 4-year period (the worst, of course, was the 89% market loss during the Great Depression).

Notice that from a valuation standpoint, there is no “tradeoff” between return and risk. Rather, depressed valuations tend to be followed by both strong long-term returns and modest subsequent losses, while extreme valuations tend to be followed by both poor long-term returns and deep subsequent losses.

Put simply, investors are not somehow rewarded for accepting higher levels of what Ben Graham described as ‘unintelligent’ risk.

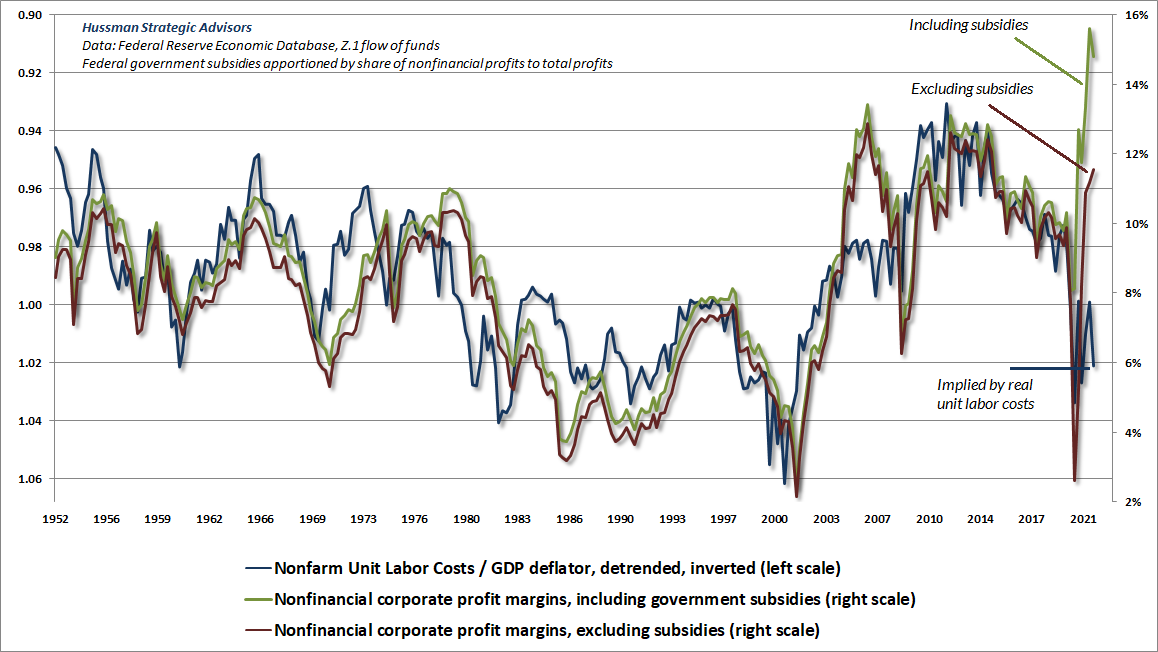

One might argue that – despite being better correlated with subsequent market returns than alterative metrics – the ratio of market capitalization to gross value-added (essentially corporate revenues) is an inappropriate measure of stock market valuations, because profit margins are currently so high. The problem here is that profit margins are high largely because of pandemic-related subsidies, and because real wage growth was so dismal coming out of the global financial crisis (another cost of Fed-induced yield-seeking speculation). The chart below offers some useful perspective on where corporate profit margins are at present, how much of that impact is attributable to fiscal support (primarily in the form of PPP provided to employers who used it to offset compensation expenses), and where profit margins may eventually settle if they again become aligned with real unit labor costs.

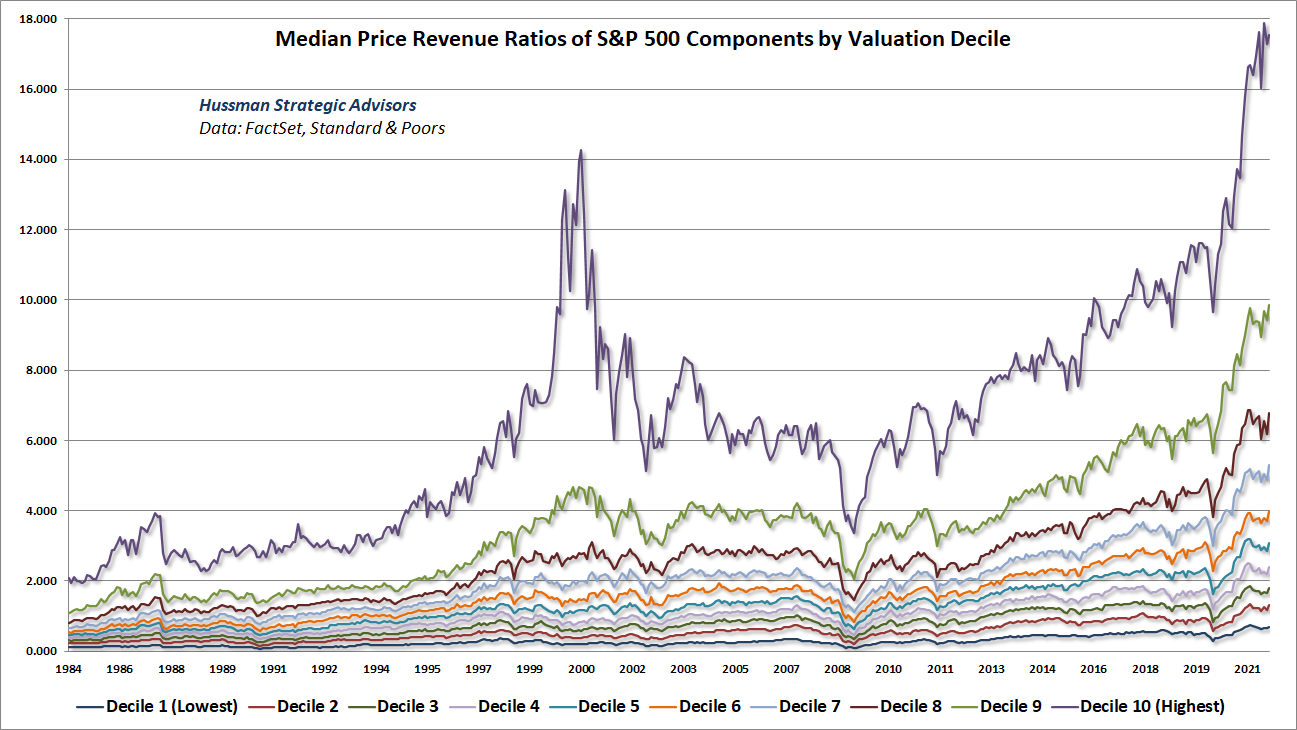

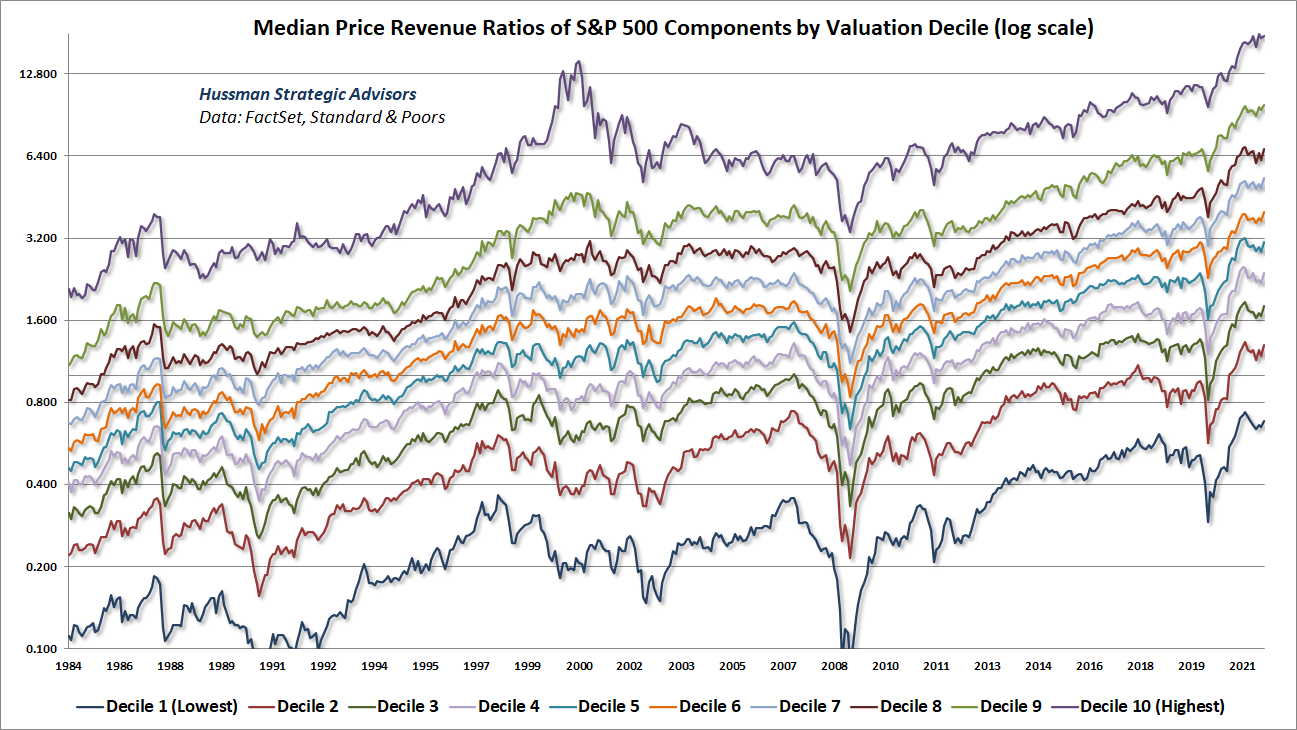

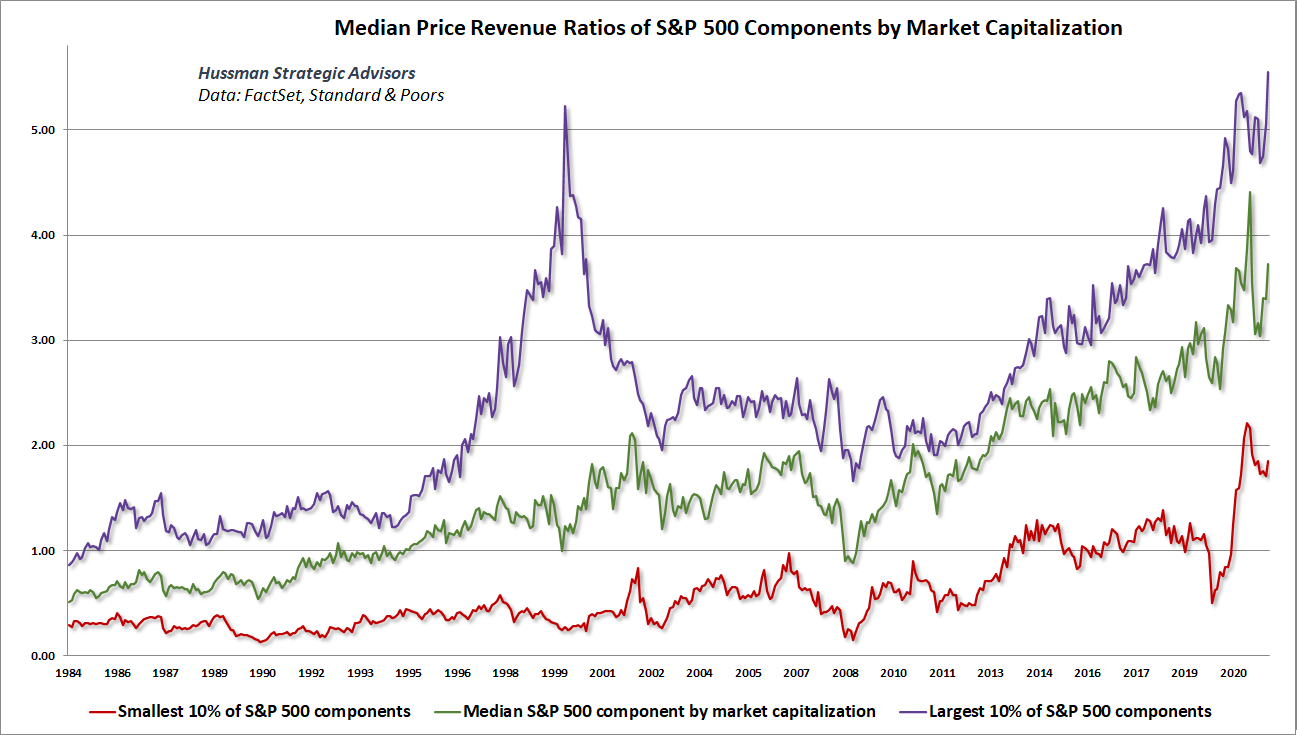

One might also argue that the elevated valuation of the equity market here is driven by a small subset of glamour technology stocks. That’s an argument we hear quite a bit, but the problem is that it’s utterly incorrect. Even excluding the most overvalued stocks, or the largest capitalization stocks, the broad market is at record extremes here.

The chart below divides S&P 500 components into ten deciles ranked by price/revenue ratio, and shows the median price/revenue ratio within each decile. At present, every one of these deciles is at or near record highs. Notably, high price/revenue groups typically reflect technology, communications, and medical stocks, while low price/revenue groups typically reflect industries like banking and retail. As a result, each line should be compared with its own history – the main question being how many of them are extremely elevated or depressed.

The chart below is the same as the preceding chart, but on log scale, which allows easier comparison of each decile with its own history.

The chart below illustrates the extreme valuation of S&P 500 components, but in this case, each decile is formed based on market capitalization. Note that while the largest capitalization stocks in the S&P 500 currently sport more extreme price/revenue ratios than at the 2000 bubble peak, so too do the S&P 500 components with the smallest market capitalizations.

A Fed-induced speculative bubble

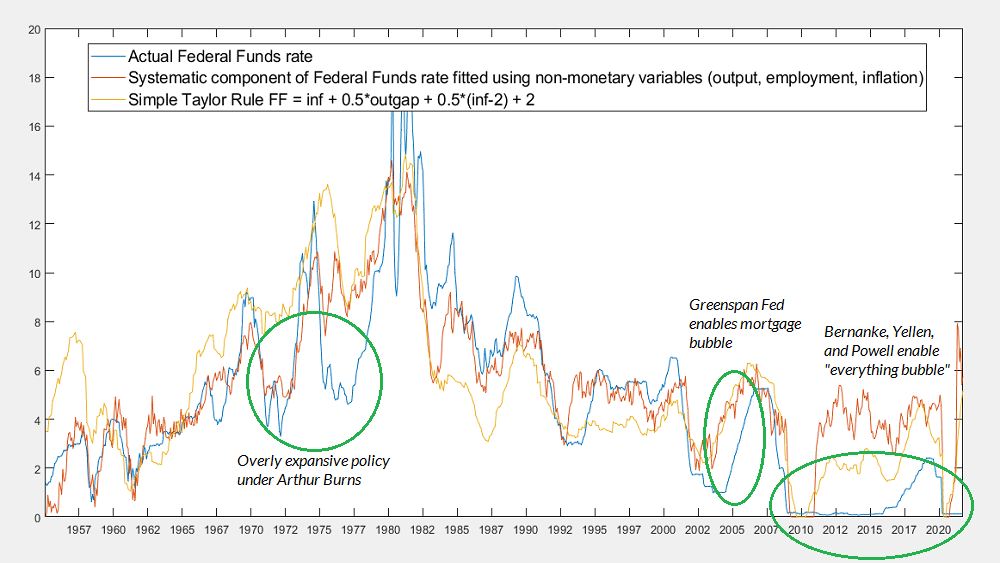

The chart below shows how deranged Federal Reserve policy has become. I use that word advisedly: de-ranged as in wildly outside of historical bounds, and also deranged as in intellectually unsound. The most important issue facing the Fed here isn’t how quickly to taper its asset purchases, or when the next rate hike should occur. The real problem for the Fed is that it has completely abandoned any semblance to a systematic policy framework, in apparent preference for a purely discretionary one.

Systematic policy means that your policy variables are correlated with, and informed by, current, lagged, and projected data on output, employment, and inflation. There are numerous systematic policy benchmarks, or a basket of them, that could be used – even as very loose guidelines – to tether Fed policy decisions to observable data. It’s easy to estimate whether deviations from systematic policy benchmarks have a large effect on subsequent economic activity (the answer is that they do not). Instead, the modern Federal Reserve has committed itself to operating monetary policy entirely by the seat of its pants.

A systematic policy would allow individuals and financial markets to anticipate the general stance of monetary policy based on observable data. Instead, the Federal Reserve has fashioned itself into a reckless circus clown handing out lollipops to diabetic toddlers. Having taught them that they will be continually appeased, regardless of the long-term consequences, even a “taper” is now met with wails of surprise, crisis, and tantrum.

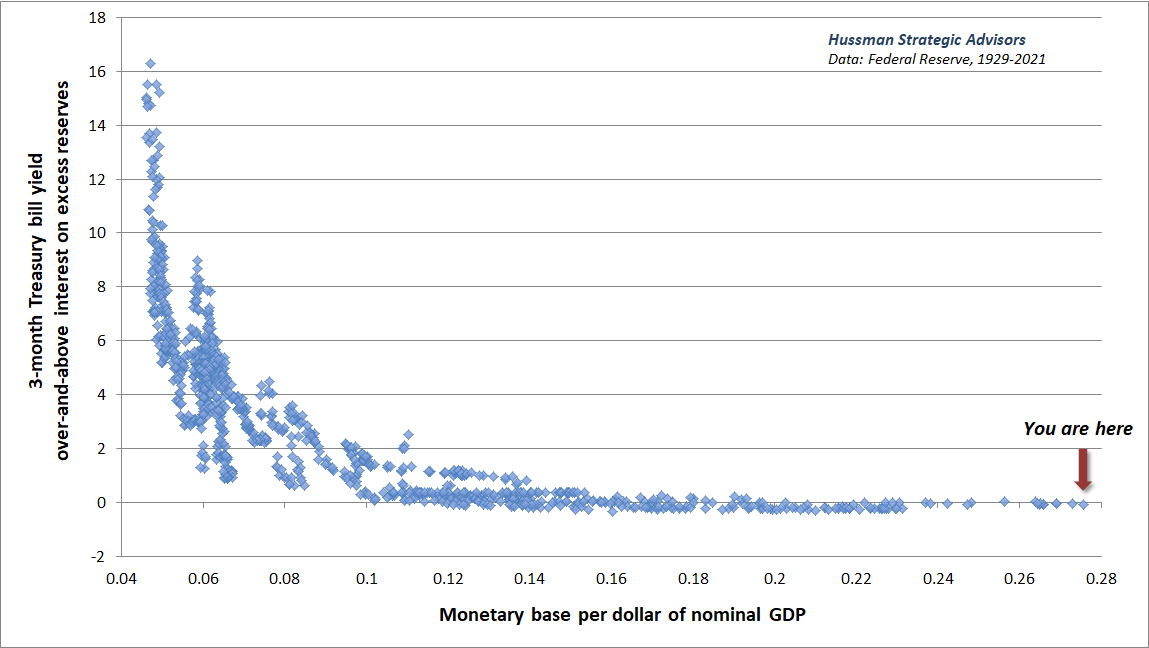

The Federal Funds rate remains pegged at zero, with the monetary base at nearly 28% of GDP. This, despite 7% CPI inflation, 3.9% unemployment, real output just 1.6% shy of the CBO estimate for potential GDP, and yield-seeking financial speculation that has driven the equity market to the highest valuations and lowest yields of any point in U.S. history outside of the 2000 market peak.

The most important issue facing the Fed here isn’t how quickly to taper its asset purchases, or when the next rate hike should occur. The real problem for the Fed is that it has completely abandoned any semblance to a systematic policy framework, in apparent preference for a purely discretionary one.

The current level of the monetary base relative to GDP is utterly at odds with Section 2A of the Federal Reserve Act, which instructs the Fed to “maintain long-run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production.” The ratio of base money to GDP never exceeded 16% before 2008. The nearest alternative to holding zero-interest base money is to hold a Treasury bill, and 16% of GDP in zero interest base money is already sufficient to drive T-bill rates to zero. Until the Federal Reserve contracts its balance sheet by half, the only way the Fed can raise short term interest rates above zero is by explicitly paying interest to banks on their excess reserves (IOER).

Keep in mind that this zero-interest money created by the Fed can change hands, and can be intermediated from one holder to another, but it doesn’t disappear by “going” anywhere or finding another “home.” It just changes hands. It’s a pile of hot potatoes that will, and must, stay in the form of zero interest cash until the Fed mops it up. That’s how the Fed has become responsible for the most pervasive speculative bubble, the most extreme level of valuation, and the greatest level of financial instability in history. The only question is how long they can keep it up, by repeatedly stomping on the accelerator and making the ultimate consequences worse.

Systematic policy means that your policy variables are correlated with, and informed by, current, lagged, and projected data on output, employment, and inflation. There are numerous systematic policy benchmarks, or a basket of them, that could be used – even as very loose guidelines – to tether Fed policy decisions to observable data. Instead, the modern Federal Reserve has committed itself to operating monetary policy entirely by the seat of its pants.

Remember also that the elevated market capitalization of stocks is not aggregate “wealth.” Every security must be held by someone until it is retired. If one investor sells at an elevated price, another investors has also bought the security at that price. In aggregate, the only thing the holder, or series of holders, will get from the security is the long-term stream of cash flows that it delivers over time. The wealth is in the cash flows. An elevated market capitalization only allows current holders to receive a transfer of savings from some other investor, who then holds the bag. No wonder that stock sales by corporate insiders have reached record extremes. So not only has the Fed enabled a speculative bubble, it has also widened the wealth gap by enabled a massive transfer of aggregate savings to the top 1%.

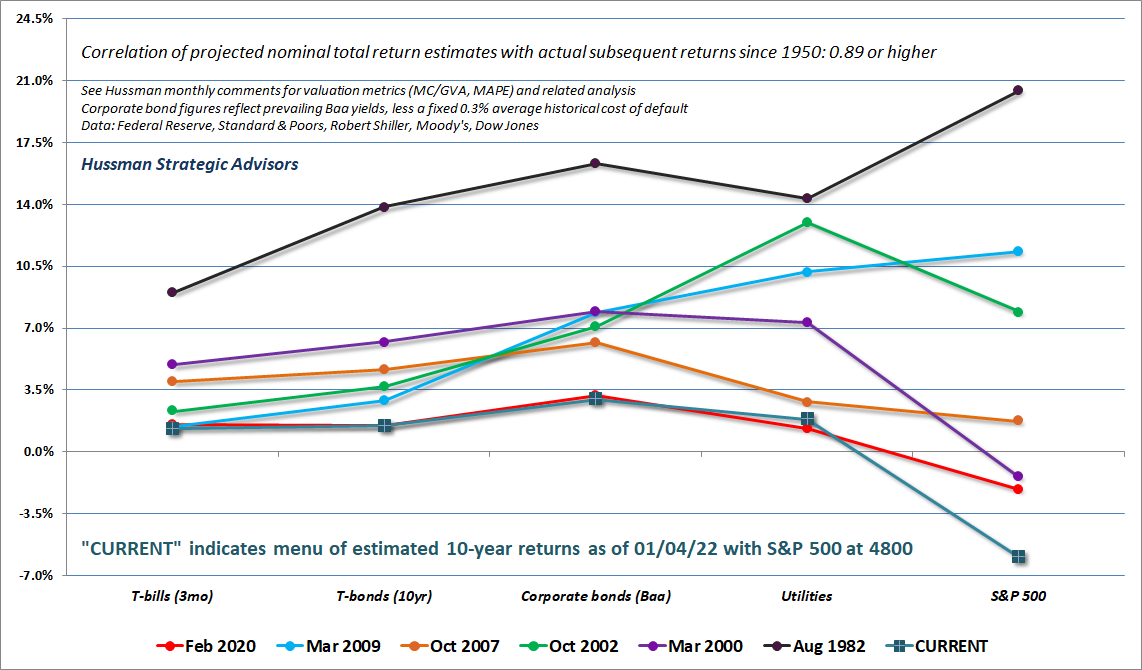

Put simply, by relentlessly depriving investors of risk-free return, the Federal Reserve has spawned an all-asset speculative bubble that we estimate will provide investors little but return-free risk. The chart below shows the menu of estimated 10-year returns across various conventional asset classes. Each line shows a different point in time, including the 1982 and 2009 market lows, and the 2000, 2007, and 2020 market highs. The current menu of estimated prospective investment returns is the worst in history.

Meanwhile, remember that easy money does not prevent periodic market losses when market internals are unfavorable. The reason is simple. When investors become risk-averse, safe, low-interest liquidity becomes a desirable asset rather than an inferior one. So creating more of the stuff doesn’t support stocks. In contrast, when investors are inclined to speculate, they psychologically rule out the possibility of capital losses. In that environment, zero-interest liquidity burns a hole in both their pockets and their souls. They feel the need to get rid of it, so they chase risky securities regardless of their valuations. Unfortunately, every dollar that a buyer brings “into” the stock market in the hands of a buyer goes “out of” the stock market in the hands of a seller.

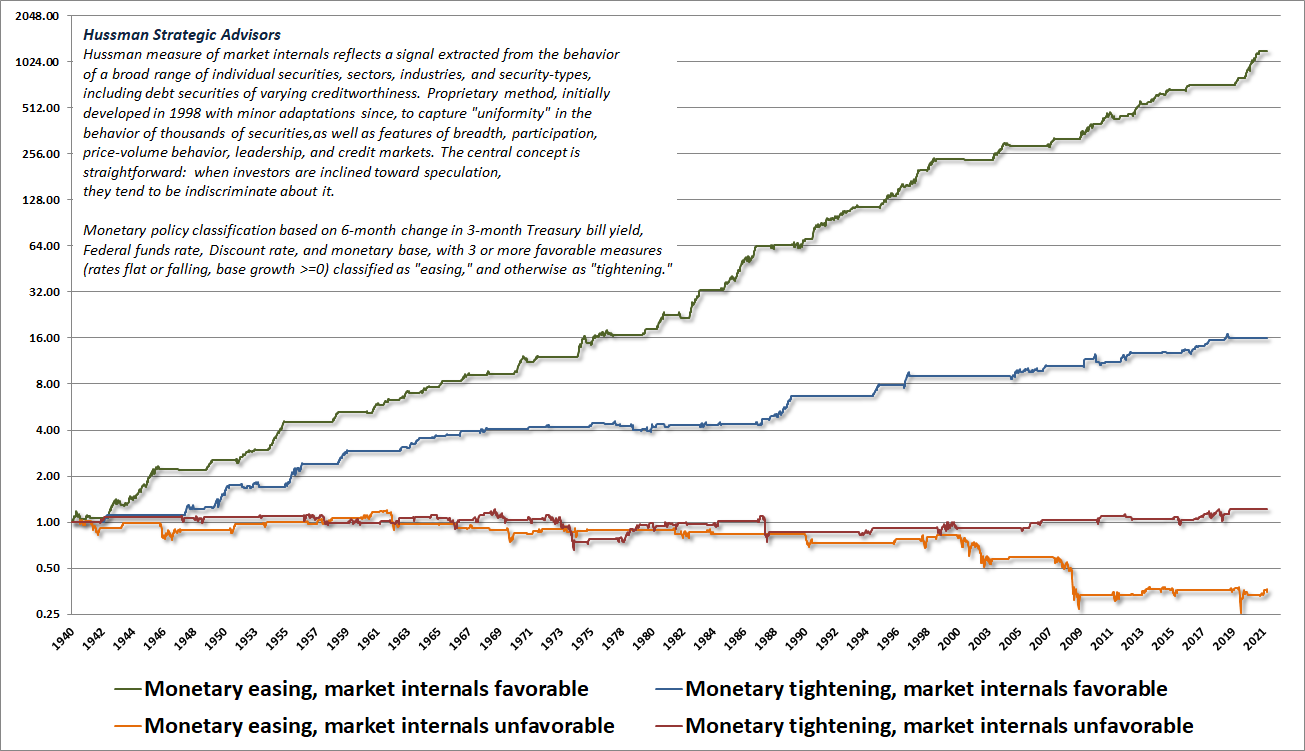

The chart below presents the cumulative total return of the S&P 500, classified into four groups based on the condition of market internals and the stance of monetary policy. The chart is historical, does not represent any investment portfolio, does not reflect valuations or other features of our investment approach, and is not an assurance of future outcomes. It’s worth noting that when investors are inclined to speculate (as gauged by favorable market internals), Fed easing can substantially amplify that speculation. But it’s also worth noting that when investors are inclined toward risk-aversion, as they were in 2000-2002 and 2007-2009, even persistent and aggressive Fed easing may not support stocks.

The deranged conduct of monetary policy in recent years has certainly forced us to adapt (see the opening quote of this comment). Our main adaptation in recent years has been to abandon the idea that Fed-induced speculation has a “limit” and instead to be content to align our outlook with the prevailing condition of observable market conditions, particularly valuations and our gauge of internals.

The thing that ‘holds the stock market up’ isn’t zero-interest liquidity, at least not in any mechanical way. It’s a particularly warped form of speculative psychology that rules out the possibility of loss, regardless of how extreme valuations have become.

– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., Maladaptive Beliefs, September 12, 2021

Taken together, we enter 2022 amid the most extreme financial bubble in U.S. history, driven by yield-seeking speculation, amplified by a Federal Reserve that has abandoned any tether to systematic monetary policy. Across history, with few exceptions – and none that worked out well – policy tools like the Fed Funds rate and the ratio of base money to GDP have typically had a reasonably strong correlation with observable economic data – unemployment, inflation, and the GDP output gap. The “policy error” of the Fed is already behind us, and can be measured by the gap between what the Fed has actually done, and what any reasonable basket of systematic policy guidelines would have suggested instead.

Data: Federal Reserve

If there was a strong relationship of reasonable effect-size between the Fed’s activist policy departures and subsequent outcomes like GDP growth and employment gains, those departures might be worth the financial distortions. Unfortunately, the “activist” component of monetary policy – the difference between actual Fed policy tools and the level implied by systematic policy guidelines – has nearly zero correlation with subsequent GDP growth or employment. As a strategy to juice the economy, activist monetary policy is almost pure noise, but has profound consequences for longer-term outcomes by enabling speculation, malinvestment, financial bubbles, and ultimately financial crises. In my view, the main consequence has been to create a speculative financial bubble that now offers investors little but return-free risk, and it will end badly. For more on systematic monetary policy guidelines like the Taylor Rule, see Bill Hester’s recent research article – Collision Course: Monetary Tightening Meets and Easy-Money Bubble.

Having correctly projected the extent of prospective market losses at the 2000 and 2007 extremes (including a March 2000 projection of an 83% loss in technology stocks), we can project that the S&P 500 would have to lose about 70% of its value here – simply to touch the run-of-the-mill valuation norms that have historically been associated with expected long-term nominal returns of about 10% annually.

Still, nothing in our discipline relies on valuations ever visiting those historical norms again. Instead, we are prepared for anything, and are content to align our investment stance with observable market conditions – primarily measures of valuation (to gauge investment merit) and market internals (to gauge speculative pressure).

In Honor and Remembrance of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Darkness cannot drive out darkness; Only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; Only love can do that.

– Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. King noted that he tried to speak on the subject below at least once a year. Preserving that tradition has always seemed an appropriate way to honor him. If you’ve never read Dr. King’s writings, this talk is a good place to start. I don’t think it’s possible to read his words without coming away better for it.

Loving Your Enemies

November 17 1957

“I want to use as a subject from which to preach this morning a very familiar subject, and it is familiar to you because I have preached from this subject twice before to my knowing in this pulpit. I try to make it a, something of a custom or tradition to preach from this passage of Scripture at least once a year, adding new insights that I develop along the way out of new experiences as I give these messages. Although the content is, the basic content is the same, new insights and new experiences naturally make for new illustrations.

“So I want to turn your attention to this subject: “Loving Your Enemies.” It’s so basic to me because it is a part of my basic philosophical and theological orientation – the whole idea of love, the whole philosophy of love. In the fifth chapter of the gospel as recorded by Saint Matthew, we read these very arresting words flowing from the lips of our Lord and Master: “Ye have heard that it has been said, ‘Thou shall love thy neighbor, and hate thine enemy.’ But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them that despitefully use you; that ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven.”

“Over the centuries, many persons have argued that this is an extremely difficult command. Many would go so far as to say that it just isn’t possible to move out into the actual practice of this glorious command. But far from being an impractical idealist, Jesus has become the practical realist. The words of this text glitter in our eyes with a new urgency. Far from being the pious injunction of a utopian dreamer, this command is an absolute necessity for the survival of our civilization. Yes, it is love that will save our world and our civilization, love even for enemies.

“Now let me hasten to say that Jesus was very serious when he gave this command; he wasn’t playing. He realized that it’s hard to love your enemies. He realized that it’s difficult to love those persons who seek to defeat you, those persons who say evil things about you. He realized that it was painfully hard, pressingly hard. But he wasn’t playing. We have the Christian and moral responsibility to seek to discover the meaning of these words, and to discover how we can live out this command, and why we should live by this command.

So this morning, as I look into your eyes, and into the eyes of all of my brothers in Alabama and all over America and over the world, I say to you, ‘I love you. I would rather die than hate you.’ And I’m foolish enough to believe that through the power of this love somewhere, men of the most recalcitrant bent will be transformed.

– Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Now first let us deal with this question, which is the practical question: How do you go about loving your enemies? I think the first thing is this: In order to love your enemies, you must begin by analyzing self. And I’m sure that seems strange to you, that I start out telling you this morning that you love your enemies by beginning with a look at self. It seems to me that that is the first and foremost way to come to an adequate discovery to the how of this situation.

“Now, I’m aware of the fact that some people will not like you, not because of something you have done to them, but they just won’t like you. But after looking at these things and admitting these things, we must face the fact that an individual might dislike us because of something that we’ve done deep down in the past, some personality attribute that we possess, something that we’ve done deep down in the past and we’ve forgotten about it; but it was that something that aroused the hate response within the individual. That is why I say, begin with yourself. There might be something within you that arouses the tragic hate response in the other individual.

“This is true in our international struggle. Democracy is the greatest form of government to my mind that man has ever conceived, but the weakness is that we have never touched it. We must face the fact that the rhythmic beat of the deep rumblings of discontent from Asia and Africa is at bottom a revolt against the imperialism and colonialism perpetuated by Western civilization all these many years.

“And this is what Jesus means when he said: “How is it that you can see the mote in your brother’s eye and not see the beam in your own eye?” And this is one of the tragedies of human nature. So we begin to love our enemies and love those persons that hate us whether in collective life or individual life by looking at ourselves.

“A second thing that an individual must do in seeking to love his enemy is to discover the element of good in his enemy, and every time you begin to hate that person and think of hating that person, realize that there is some good there and look at those good points which will over-balance the bad points.

“Somehow the “isness” of our present nature is out of harmony with the eternal “oughtness” that forever confronts us. And this simply means this: That within the best of us, there is some evil, and within the worst of us, there is some good. When we come to see this, we take a different attitude toward individuals. The person who hates you most has some good in him; even the nation that hates you most has some good in it; even the race that hates you most has some good in it. And when you come to the point that you look in the face of every man and see deep down within him what religion calls “the image of God,” you begin to love him in spite of. No matter what he does, you see God’s image there. There is an element of goodness that he can never slough off. Discover the element of good in your enemy. And as you seek to hate him, find the center of goodness and place your attention there and you will take a new attitude.

“Another way that you love your enemy is this: When the opportunity presents itself for you to defeat your enemy, that is the time which you must not do it. There will come a time, in many instances, when the person who hates you most, the person who has misused you most, the person who has gossiped about you most, the person who has spread false rumors about you most, there will come a time when you will have an opportunity to defeat that person. It might be in terms of a recommendation for a job; it might be in terms of helping that person to make some move in life. That’s the time you must do it. That is the meaning of love. In the final analysis, love is not this sentimental something that we talk about. It’s not merely an emotional something. Love is creative, understanding goodwill for all men. It is the refusal to defeat any individual. When you rise to the level of love, of its great beauty and power, you seek only to defeat evil systems. Individuals who happen to be caught up in that system, you love, but you seek to defeat the system.

Within the best of us, there is some evil, and within the worst of us, there is some good. The person who hates you most has some good in him; even the nation that hates you most has some good in it; even the race that hates you most has some good in it… No matter what he does, you see God’s image there. There is an element of goodness that he can never slough off.

“The Greek language, as I’ve said so often before, is very powerful at this point. It comes to our aid beautifully in giving us the real meaning and depth of the whole philosophy of love. And I think it is quite apropos at this point, for you see the Greek language has three words for love, interestingly enough. It talks about love as eros. That’s one word for love. Eros is a sort of, aesthetic love. Plato talks about it a great deal in his dialogues, a sort of yearning of the soul for the realm of the gods. And it’s come to us to be a sort of romantic love, though it’s a beautiful love. Everybody has experienced eros in all of its beauty when you find some individual that is attractive to you and that you pour out all of your like and your love on that individual. That is eros, you see, and it’s a powerful, beautiful love that is given to us through all of the beauty of literature; we read about it.

“Then the Greek language talks about philia, and that’s another type of love that’s also beautiful. It is a sort of intimate affection between personal friends. And this is the type of love that you have for those persons that you’re friendly with, your intimate friends, or people that you call on the telephone and you go by to have dinner with, and your roommate in college and that type of thing. It’s a sort of reciprocal love. On this level, you like a person because that person likes you. You love on this level, because you are loved. You love on this level, because there’s something about the person you love that is likeable to you. This too is a beautiful love. You can communicate with a person; you have certain things in common; you like to do things together. This is philia.

“The Greek language comes out with another word for love. It is the word agape. And agape is more than eros; agape is more than philia; agape is something of the understanding, creative, redemptive goodwill for all men. It is a love that seeks nothing in return. It is an overflowing love; it’s what theologians would call the love of God working in the lives of men. And when you rise to love on this level, you begin to love men, not because they are likeable, but because God loves them. You look at every man, and you love him because you know God loves him. And he might be the worst person you’ve ever seen.

“And this is what Jesus means, I think, in this very passage when he says, “Love your enemy.” And it’s significant that he does not say, “Like your enemy.” Like is a sentimental something, an affectionate something. There are a lot of people that I find it difficult to like. I don’t like what they do to me. I don’t like what they say about me and other people. I don’t like their attitudes. I don’t like some of the things they’re doing. I don’t like them. But Jesus says love them. And love is greater than like. Love is understanding, redemptive goodwill for all men, so that you love everybody, because God loves them. You refuse to do anything that will defeat an individual, because you have agape in your soul. And here you come to the point that you love the individual who does the evil deed, while hating the deed that the person does. This is what Jesus means when he says, “Love your enemy.” This is the way to do it. When the opportunity presents itself when you can defeat your enemy, you must not do it.

“Now for the few moments left, let us move from the practical how to the theoretical why. It’s not only necessary to know how to go about loving your enemies, but also to go down into the question of why we should love our enemies. I think the first reason that we should love our enemies, and I think this was at the very center of Jesus’ thinking, is this: that hate for hate only intensifies the existence of hate and evil in the universe. If I hit you and you hit me and I hit you back and you hit me back and go on, you see, that goes on ad infinitum. It just never ends. Somewhere somebody must have a little sense, and that’s the strong person. The strong person is the person who can cut off the chain of hate, the chain of evil. And that is the tragedy of hate – that it doesn’t cut it off. It only intensifies the existence of hate and evil in the universe. Somebody must have religion enough and morality enough to cut it off and inject within the very structure of the universe that strong and powerful element of love.

“I think I mentioned before that sometime ago my brother and I were driving one evening to Chattanooga, Tennessee, from Atlanta. He was driving the car. And for some reason the drivers were very discourteous that night. They didn’t dim their lights; hardly any driver that passed by dimmed his lights. And I remember very vividly, my brother A. D. looked over and in a tone of anger said: “I know what I’m going to do. The next car that comes along here and refuses to dim the lights, I’m going to fail to dim mine and pour them on in all of their power.” And I looked at him right quick and said: “Oh no, don’t do that. There’d be too much light on this highway, and it will end up in mutual destruction for all. Somebody got to have some sense on this highway.”

“Somebody must have sense enough to dim the lights, and that is the trouble, isn’t it? That as all of the civilizations of the world move up the highway of history, so many civilizations, having looked at other civilizations that refused to dim the lights, and they decided to refuse to dim theirs. And Toynbee tells that out of the twenty-two civilizations that have risen up, all but about seven have found themselves in the junk heap of destruction. It is because civilizations fail to have sense enough to dim the lights. And if somebody doesn’t have sense enough to turn on the dim and beautiful and powerful lights of love in this world, the whole of our civilization will be plunged into the abyss of destruction. And we will all end up destroyed because nobody had any sense on the highway of history.

The strong person is the person who can cut off the chain of hate, the chain of evil. And that is the tragedy of hate – that it doesn’t cut it off. It only intensifies the existence of hate and evil in the universe. Somebody must have religion enough and morality enough to cut it off and inject within the very structure of the universe that strong and powerful element of love.

“Somewhere somebody must have some sense. Men must see that force begets force, hate begets hate, toughness begets toughness. And it is all a descending spiral, ultimately ending in destruction for all and everybody. Somebody must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate and the chain of evil in the universe. And you do that by love.

“There’s another reason why you should love your enemies, and that is because hate distorts the personality of the hater. We usually think of what hate does for the individual hated or the individuals hated or the groups hated. But it is even more tragic, it is even more ruinous and injurious to the individual who hates. You just begin hating somebody, and you will begin to do irrational things. You can’t see straight when you hate. You can’t walk straight when you hate. You can’t stand upright. Your vision is distorted. There is nothing more tragic than to see an individual whose heart is filled with hate. He comes to the point that he becomes a pathological case. For the person who hates, you can stand up and see a person and that person can be beautiful, and you will call them ugly. For the person who hates, the beautiful becomes ugly and the ugly becomes beautiful. For the person who hates, the good becomes bad and the bad becomes good. For the person who hates, the true becomes false and the false becomes true. That’s what hate does. You can’t see right. The symbol of objectivity is lost. Hate destroys the very structure of the personality of the hater.

“The way to be integrated with yourself is be sure that you meet every situation of life with an abounding love. Never hate, because it ends up in tragic, neurotic responses. Psychologists and psychiatrists are telling us today that the more we hate, the more we develop guilt feelings and we begin to subconsciously repress or consciously suppress certain emotions, and they all stack up in our subconscious selves and make for tragic, neurotic responses. And may this not be the neuroses of many individuals as they confront life that that is an element of hate there. And modern psychology is calling on us now to love. But long before modern psychology came into being, the world’s greatest psychologist who walked around the hills of Galilee told us to love. He looked at men and said: “Love your enemies; don’t hate anybody.” It’s not enough – to love your friends – because when you start hating anybody, it destroys the very center of your creative response to life and the universe; so love everybody. Hate at any point is a cancer that gnaws away at the very vital center of your life and your existence. It is like eroding acid that eats away the best and the objective center of your life. So Jesus says love, because hate destroys the hater as well as the hated.

“Now there is a final reason I think that Jesus says, “Love your enemies.” It is this: that love has within it a redemptive power. And there is a power there that eventually transforms individuals. That’s why Jesus says, “Love your enemies.” Because if you hate your enemies, you have no way to redeem and to transform your enemies. But if you love your enemies, you will discover that at the very root of love is the power of redemption. You just keep loving people and keep loving them, even though they’re mistreating you. Here’s the person who is a neighbor, and this person is doing something wrong to you and all of that. Just keep being friendly to that person. Keep loving them. Don’t do anything to embarrass them. Just keep loving them, and they can’t stand it too long. Oh, they react in many ways in the beginning. They react with bitterness because they’re mad because you love them like that. They react with guilt feelings, and sometimes they’ll hate you a little more at that transition period, but just keep loving them. And by the power of your love they will break down under the load. That’s love, you see. It is redemptive, and this is why Jesus says love. There’s something about love that builds up and is creative. There is something about hate that tears down and is destructive. So love your enemies.

“There is a power in love that our world has not discovered yet. Jesus discovered it centuries ago. Mahatma Gandhi of India discovered it a few years ago, but most men and most women never discover it. For they believe in hitting for hitting; they believe in an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth; they believe in hating for hating; but Jesus comes to us and says, “This isn’t the way.”

“As we look out across the years and across the generations, let us develop and move right here. We must discover the power of love, the power, the redemptive power of love. And when we discover that we will be able to make of this old world a new world. We will be able to make men better. Love is the only way. Jesus discovered that.

“And our civilization must discover that. Individuals must discover that as they deal with other individuals. There is a little tree planted on a little hill and on that tree hangs the most influential character that ever came in this world. But never feel that that tree is a meaningless drama that took place on the stages of history. Oh no, it is a telescope through which we look out into the long vista of eternity, and see the love of God breaking forth into time. It is an eternal reminder to a power-drunk generation that love is the only way. It is an eternal reminder to a generation depending on nuclear and atomic energy, a generation depending on physical violence, that love is the only creative, redemptive, transforming power in the universe.

“So this morning, as I look into your eyes, and into the eyes of all of my brothers in Alabama and all over America and over the world, I say to you, “I love you. I would rather die than hate you.” And I’m foolish enough to believe that through the power of this love somewhere, men of the most recalcitrant bent will be transformed. And then we will be in God’s kingdom.”

Keep Me Informed

Please enter your email address to be notified of new content, including market commentary and special updates.

Thank you for your interest in the Hussman Funds.

100% Spam-free. No list sharing. No solicitations. Opt-out anytime with one click.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive news and commentary, at no cost, from Hussman Strategic Advisors, News & Commentary, Cincinnati OH, 45246. https://www.hussmanfunds.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact.

The foregoing comments represent the general investment analysis and economic views of the Advisor, and are provided solely for the purpose of information, instruction and discourse.

Prospectuses for the Hussman Strategic Growth Fund, the Hussman Strategic Total Return Fund, the Hussman Strategic International Fund, and the Hussman Strategic Allocation Fund, as well as Fund reports and other information, are available by clicking “The Funds” menu button from any page of this website.

Estimates of prospective return and risk for equities, bonds, and other financial markets are forward-looking statements based the analysis and reasonable beliefs of Hussman Strategic Advisors. They are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of the prospective returns of any of the Hussman Funds. Actual returns may differ substantially from the estimates provided. Estimates of prospective long-term returns for the S&P 500 reflect our standard valuation methodology, focusing on the relationship between current market prices and earnings, dividends and other fundamentals, adjusted for variability over the economic cycle.